From field notes to cassette tapes, one project is preserving language materials that would otherwise be lost.

By Nick Thieberger, University of Melbourne, Australia

Linguists and musicologists at three Australian universities are working together to preserve rare recordings and make them accessible to communities across the Pacific and beyond.

By Nick Thieberger, University of Melbourne, Australia

Of the 7,000 languages spoken in the world today, there are records of only a fraction. Think about your own language and how easily you can find information in or about it. If you speak one of the major languages, there is no doubt a wealth of material from which to choose. But for many languages, the opposite is true.

Each language offers a new window into how human societies communicate and create their world. For those that are unlikely to be spoken by a new generation of speakers, or have ceased to be spoken at all, records are particularly important as they may be the only permanent source of information about that language or culture.

In the past, the ethics of working with speakers of these languages was not taken as seriously as it is today, often resulting in an extractive process that had little benefit to the communities themselves. A key change in methodology over the past generation has led to far more collaborative research projects between speakers and academics, and a focus on making materials that can be used by communities of speakers.

These materials include books drawn from recorded and transcribed local oral tradition. They include spoken histories, dictionaries, and recorded song. But creating materials isn’t the whole story.

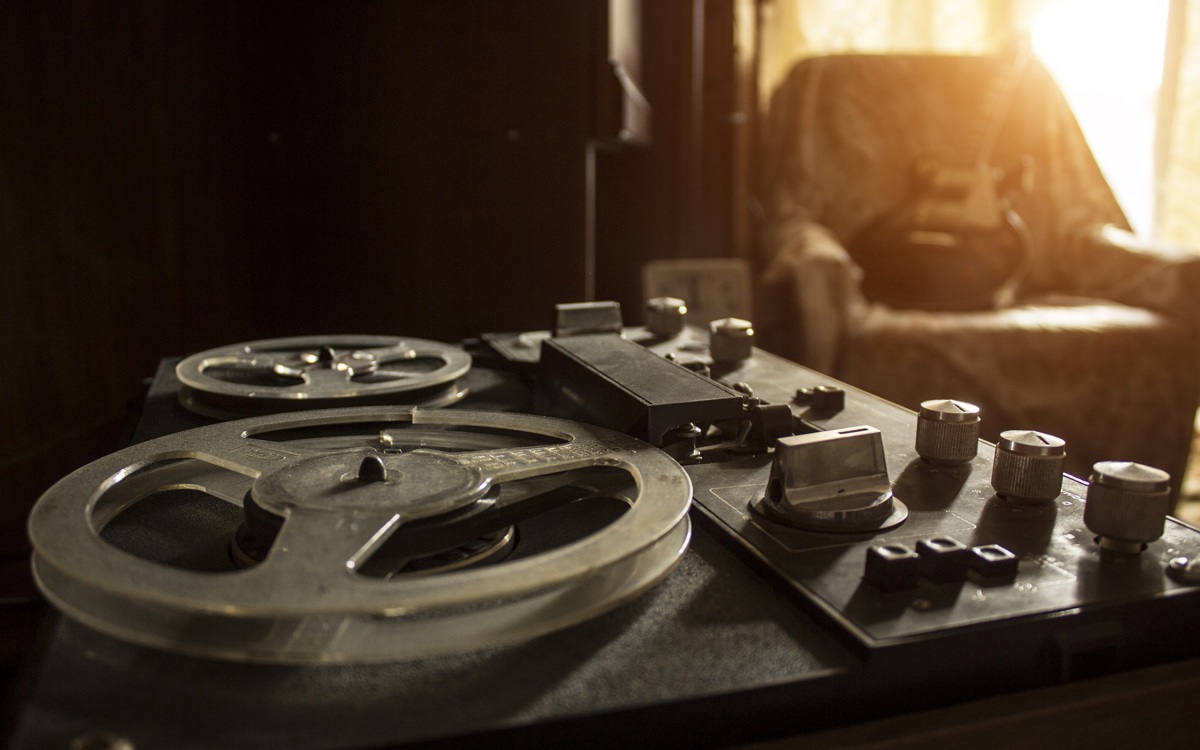

Where materials exist, it can be difficult to ensure they remain accessible over time: books fall apart, photographs fade, and cassette tapes can no longer be played.

Preservation and access

Where materials exist, it can be difficult to ensure they remain accessible over time: books fall apart, photographs fade, and cassette tapes can no longer be played. In the offices and deceased estates of linguists from years gone by, we found many tape collections with no provision made for their preservation. With analog tapes, there is often only a narrow window of time before they become unplayable, due to both the fragility of the media and the increasing scarcity of machines on which they can be played.

To keep these materials available, we set up the Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC), a collaboration between linguists and musicologists at the University of Melbourne, the University of Sydney, and the Australian National University. A primary goal is to safely preserve material that would otherwise be lost. In this way, we can make field recordings available to the people and communities from which they originate, as well as to their descendants.

Our aim was to find existing materials in or about the many small languages of our region, and digitise them with enough metadata to make them findable. This included the preservation of heritage materials such as the fieldnotes of linguists working more than a century ago. With initial funding from the Australian Research Council, we began the process of converting cassette tapes to digital formats. At the same time, we developed a metadata system to describe these tapes, and a database to keep track of all the materials. Currently, we have more than 280,000 items in the collection, including over 10,000 hours of audio recordings. The archive is 58 terabytes and represents more than 1,200 languages.

Our catalogue provides feeds that are harvested by external services, such as the Open Language Archives Community, which increases the findability of an item in our collection. This means that even the most remote user who has internet access can find records.

For people with little or no internet access, we have explored ways to provide local copies of these records. An obvious way of doing this is to send all items for a given language, or a hard disk of the materials, to the local cultural centre or museum. But what about those places that don’t have computers and so can’t use a hard disk? To get around this, we have built local wifi transmitters with hard disks that can be used in this situation. The wifi transmitter is called a Raspberry Pi and costs less than $100. It can be set up to transmit within a small local area and allows materials to be accessed on mobile phones or tablets.

Expanding our remit

PARADISEC has also become a cutting-edge research programme in itself, providing citable forms of primary data that are necessary to allow researchers to build their analysis with verifiable results. In the past, we could write about the way a sentence is pronounced but provide no access to the audio recording. Readers could rightly question our analysis, and even whether the sentence was actually produced in natural speech at all. Now, however, they can listen to the sentence in its context in a citable archived file. What’s more, they can go on to explore new aspects of the data that weren’t considered by the original researcher.

In my own work, for example, my records of Nafsan – a language spoken in Vanuatu – include some 30 hours of recordings with transcripts, fieldnotes, photos, videos, and scanned historical texts dating back to the 1860s. Once this material is digitised, other researchers are able to work on it, examining aspects of the language that I did not cover in detail in my work. Who knows, perhaps an ornithologist will one day listen to my recordings of oral tradition to identify any bird calls captured there.

Having built a relatively simple system for adding new items to our archive, we now receive numerous new materials from around the world. These valuable recordings are not always ‘archive ready’. Some are made on poor equipment or where the microphone was too far from the speaker, meaning little is audible. Transcripts on paper can’t be searched on a computer, and transcripts typed on older machines don’t include valuable timecodes that enable specific sections, words, or stories to be easily found.

This has led us to focus on providing training in new recording techniques, so that the process of recording, transcription, and annotation all result in records that can be reused later on. We are keen to help current fieldworkers to adopt methods that give them greater access to their own recordings, while, at the same time, making their collections searchable. As well as researchers, we also train community members to do their own recordings.

These newer methods for transcription insert timecodes for each chunk of a transcript, allowing users to cite down to the level of a word or sentence. Articles referencing a particular story or sentence can now include a direct link to hear those same words spoken aloud.

At a time when many languages are increasingly endangered, it is our role as academics to ensure that the records we make in those languages do not themselves become endangered. We can do this by creating and contributing to archives that will keep the records alive and available into the future.

Dr Nick Thieberger is an Associate Professor and ARC Future Fellow in the School of Languages and Linguistics, University of Melbourne, Australia. He is also Director of the Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC).

PARADISEC’s ‘Lost and found’ project is seeking new collections in need of digitisation from around the world. Visit www.paradisec.org.au/help-us-locate-endangered-recordings

Images (from top): Rudenkois at Shutterstock; Julia Miller