The COVID-19 pandemic has left many struggling with their mental health. But research from Hong Kong also points to our capacity for growth. By Joseph Lau, Chinese University of Hong Kong

The COVID-19 pandemic has left many struggling with their mental health. But research also points to our capacity for growth and altruism in the face of adversity.

By Joseph TF Lau, Chinese University of Hong Kong

COVID-19 has plunged the world into a state of uncertainty. As the slow emergence from lockdown begins, many warn of a looming mental health crisis as the psychological impact of the pandemic shifts into focus. While some countries may be experiencing the full effects of a major pandemic for the first time in decades, we in Hong Kong can draw on our experiences of the SARS outbreak to give us a head start in understanding how and why pandemics affect our mental health.

Stressors and unknowns

An important reason why outbreaks like COVID-19 pose such a significant threat to wellbeing is that they increase the risk factors – known as stressors – which contribute to poor mental health, while simultaneously limiting those aspects of life which can otherwise help to protect our emotional wellbeing.

Lockdowns, social distancing, quarantines, travel bans, and school closures have turned normal life upside down and are all stressors in themselves. But they also increase the risk of isolation and loneliness – potent risk factors for mental health problems. Studies tell us that social distancing and working from home can take a toll on healthy lifestyle habits that may otherwise ward against a low mood, such as physical activity, a healthy diet, and good sleep. Importantly, the quality of social relationships and support networks is changed by social distancing at a time when social support is more important than ever.

And then comes the uncertainty. COVID-19 is an unknown. There seem to be more questions than answers. It is highly uncertain how long the pandemic, and the disruption it brings to our lives, will last. With it comes uncertainty about jobs, health, and money. These unknowns can feel dangerous and uncomfortable, as we wonder when it will ever end.

Finally, COVID-19 has become mixed up with politics, both international and domestic. Science seems to be quarrelling aloud with politics and economics. This intrusion of politics into the health arena has complicated policymaking and public responses to COVID-19, and caused dissatisfaction and rifts within and among governments.

Our research, conducted prior to the pandemic, suggests that concerns or distress around political developments (such as those which sparked Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement) can have a significant effect on public mental health. This too may exacerbate the emotional distress caused by COVID-19.

Thoughts and actions

To understand how we react to these unknowns, it’s useful to think of the different ways in which we respond to a threat like COVID-19. The first is our cognitive response, which refers to our beliefs and perceptions about an illness – its severity, its consequences, its risk to ourselves, or our trust in government measures. Next comes our behavioural responses, such as coping strategies, help-seeking, or preventative measures. And finally, our psychological response – such emotional distress, anxiety and depression.

Crucially, these three types of response are interrelated. In other words, our beliefs and perceptions of an illness affect how we behave and feel. Meanwhile, feelings of worry, anger, or blame can have a negative effect on our behaviour or beliefs. In other words, our perceptions or beliefs about an illness directly influence our coping strategies, which in turn influence outcomes.

This highlights the importance of effective health communication: the stimulus of a pandemic such as COVID-19 may lead to false or irrational fears which inflate the negative consequences and cause emotional distress. But it also shows that it’s vital to look at the interrelationships between perceptions, coping behaviours, and mental distress, rather than viewing these in isolation.

Disadvantage and discrimination

While the pandemic affects us all, its impacts are not equally felt. Disadvantaged groups – homeless people, refugees, migrant workers, and people living in poverty – endure higher risks combined with reduced access to protective resources and mental health support. Many elderly and vulnerable people – and particularly those with chronic illnesses – have been increasingly isolated from family members and social support. Communities in many of the world’s poorest countries will find their livelihoods and basic food security under threat, as vital crops go unharvested. And health workers everywhere face exhaustion and burnout. For many of these groups, their mental health needs have been overlooked and understudied.

Discrimination is another insidious by-product of a pandemic. During the SARS outbreak, many patients experienced discrimination that, in turn, led to depression. In the present pandemic, large numbers of people are under quarantine and our research in China has detected prevalent perceived discrimination and depression in this group. Geographic-based discrimination also inflames the situation, as politicians resort to ‘finger-pointing’, associating blame with the geographic origin of the disease.

Recovery and growth

In 2003, the SARS outbreak took a devastating toll on Hong Kong, the legacies of which are still palpable today. The community’s mental health was badly hit by post-traumatic stress, sleeping problems, increased drinking and smoking, family and financial stress, and feelings of horror, helplessness, and anxiety.

But alongside these, a study by the Chinese University of Hong Kong uncovered something perhaps more surprising: notwithstanding its destructive impact, the pandemic appeared to have brought about some positive impacts on social and family connections, mental health awareness, and more. These seemed to coexist with, or even reduce, some of the negative impacts that were experienced.

In our study, 60% of respondents said that they cared more about the feelings of their family members as a result of the outbreak. Around 40% said they found their friends and family more supportive and more willing to share their feelings. Up to 40% said they took more time for rest, relaxation or exercise; and around two-thirds said they now paid more attention to their mental health.

Some of these positive shifts may have served as a cushion against the negative impacts of SARS. It is also possible that those who were adversely affected ‘learned’ to value their family, friends, and mental health more than before.

Like SARS, COVID-19 may reveal some positive changes: people with busy lifestyles slowing down a bit; families spending more time together; altruistic behaviours and appreciation of others. A pandemic may overthrow some untested assumptions in life, and offer an opportunity to re-evaluate one’s relationships with others and meaning in life.

An important phenomenon is that of post-traumatic growth – something that has been consistently reported in the aftermath of disasters and traumatic events, including SARS in Hong Kong. In the wake of adversity or trauma, some people start to experience new possibilities, greater personal strength, spiritual and relationship changes, and a renewed appreciation of life.

The need for collaboration

The global nature of the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for more international cross-border research. There are, and will be, lots of piecemeal and incomparable research taking place and it’s a pity that we may miss the chance to gain a systematic global understanding of the impact of the pandemic on mental health. A truly international research project – one that captures the common features of governmental measures but also allows for cultural differences, and that focuses both on the general population and disadvantaged groups – would be meaningful and important.

At the Chinese University of Hong Kong, our research centre is working hard to understand population-based behavioural and emotional responses to large-scale emerging infectious diseases. We have published over 20 papers on topics related to SARS and H1N1, and are working to learn more about COVID-19 and to develop metrics to measure its impact on mental health. We look forward to collaborating with international researchers as, together, we strive to understand and alleviate the long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our health and happiness.

Professor Joseph TF Lau is Professor and Associate Director at the JC School of Public Health and Primary Care at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and Head of the Division of Behavioral Health and Health Promotion.

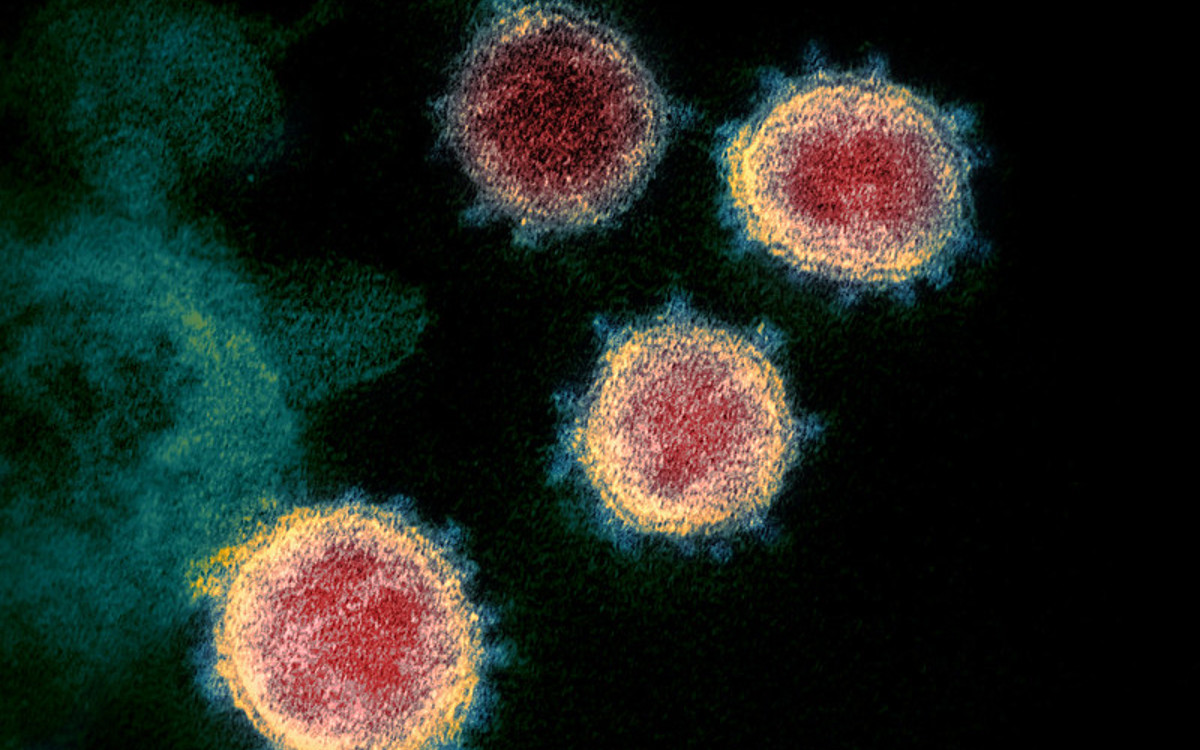

Images (from top): Electron microscope image of SARS-CoV-2 by NIAID and 3D print of virus particle by NIH, both licensed under CC BY 2.0. SARS memorial by Zytsndley Homea, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

ACU Digital Now is our commitment to ensuring that our vibrant global network continues to thrive during the COVID-19 pandemic and into the future.